Arcade is pleased to present an online augmented reality exhibition of painting curated by Luca Bertolo, kindly hosted at VORTIC COLLECT as part of the LONDON COLLECTIVE.

Some months ago, while driving I was listening to an Italian radio channel. A writer or an artist, I can’t remember, was being interviewed. It was fine, but somehow too fine; such things you then easily forget. Anyway, at one point the word pericolante was spoken. It hit me right away and by now is the only thing I precisely remember of that interview. I got to my studio, wrote it down on a slip of paper and then pinned it on the wall.

Unlike its English equivalents – teetering, precarious, shaky, wobbly, uncertain, ramshackle – pericolante contains the word pericolo, that is danger. In Italy, you would typically find it written on signs nearby unsafe, rickety (here two additional possible translations!) buildings. I kept looking over to that slip of paper and ruminated. Why do artists so often speak of ‘running the risk’ while doing such safe work as theirs is – I mean, compared to other jobs like miners, construction workers, soldiers? Indeed artists tend to describe actions like smearing some red on a green field as something really thrilling, as something dangerous. Funny as they might at times appear, artists are neither more stupid nor more paranoiac than the average of human beings. So, which kind of danger do they mean?

Because I’m a painter and for the sake of simplicity, I’ll restrict myself to painting. While meaning a peculiar object, ‘painting’ is also the gerund of a verb which expresses a peculiar activity. Such an activity has a long cultural tradition behind itself, which I won’t address here though. It’s enough of a big task to recall to our mind the very moment in which a brush, loaded with paint, traces a line (or a spot, a geometric figure, even some lettering) across a white rectangle. Let’s watch this in slow motion: 1) little by little the brush unloads itself – of colored matter, of energy, of figurative potential; 2) all of a sudden, the white-dead area turns to be lively, enters the magical domain of semiotics. Nevertheless, a constellation of signs does not necessarily excite our senses & intellect at once. Often it doesn’t. I would like to focus on the case in which in a single painting both options seem equally open. It might be true that all good paintings express a kind of a precarious balance of these options, but some paintings show that more clearly than others.

Let’s now think of a Morandi’s still life: why should the outline of a dusty bottle quiver? Could it be due to some kind of fear (of the bottle: animism; of the painter: the eternal beginner)? Or could it signal some sort of danger that threatens us all? Here’s a possible answer: the line quivers because it encircles the precarious meaning we give (we need to give) to what we see. If anything, we need to believe there is a world out there, to which art in some way refers (so called abstraction is no exception). A bottle which stops looking like a bottle might suddenly metamorphose into something scary, or into a non-sense. Morandi’s evanescent forms are at one end of a scale whose opposite pole is too much description, too much certainty. This pole may offer immediate gratification to the viewer, but it usually causes boredom after a while, a loss of liveliness, a kind of ‘death’. On the contrary, the painting I’m focusing on in this show explores the enigmatic borderland between “living” and “dying” images, and shows us the precarious status of any intelligent, energetic mark, always in danger of ranking down to a stupid, apathetic mark (or the other way around). While it does not necessarily represent ‘reality’, art does call for being taken as a metaphor of ‘reality’. Hence, I guess, the danger and the risks artists talk about.

For this show I have dramatically restricted my choice to a little, beautiful bunch of colleagues: I admire them all and some have, if differently, influenced my own work. Also, importantly for me, I’ve had the pleasure to know them personally. Winifred Nicholson, who died in 1981 (I was thirteen then, living in Brazil and planning to become every sort of professional but an artist) is obviously an exception. But since I discovered her work in 2006 at Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge, I proudly considered her among my favourite painters, and a pinned postcard reproducing a wonderful landscape of hers has followed me in three different studios since then. I’m particularly happy that Walter Swennen agreed to contribute to this show. I was so lucky to visit him last year. While drinking tea in his kitchen, we randomly talked about Titian, Max Stirner, and the importance and the danger of any painting’s reproductions. Swennen’s unique bitter humour is only comparable to his kindness. And here’s a sentence of his, which peeps out from the wall behind my computer: ‘ Making a painting is to transform nonsense into an enigma’.

LUCA BERTOLO June 2020

London Collective is a new section on the Vortic Collect app, bringing together 40 of the UK’s leading commercial galleries to present exhibitions on the new extended reality app for the art world. In the London Collective section of the Vortic Collect app, galleries will show specially curated presentations, providing them with an additional virtual space to complement their physical gallery programmes. The new initiative enables galleries to support one another by sharing their audiences and enables visitors to simulate the experience of visiting multiple London gallery locations.

The Vortic Collect app is available to download from the App Store and the Vortic VR app will be available for download from the Oculus Store from late summer 2020.

Luca Bertolo (1968, Milan, IT)

“Bertolo takes the painter’s irresolvable quest for subject matter—that futile, ceaseless, and foolhardy task—and gives it form. This is, in part, his project: he gives form to the otherwise empty desire to make a new painting, about the futility of bestowing too much meaning on any particular image or idea. Painters start every day at the bottom of the same hill, looking up. But you must not give up on the repeated, daily need to push the paint around the canvas, the pleasure and anguish of the daily reset, the search for something to paint. And just as Albert Camus argued that we must imagine Sisyphus as happy, Bertolo’s oeuvre argues that in painting’s lack of telos we might find delight, intelligence, wit, and a reason to keep painting. Bertolo takes Auden’s apparent nihilism and reinvents it as a generative paradox: painting makes nothing happen. In Bertolo’s hands, painting becomes the agent of nothingness, its activator. From nothing, something will come. But what?”

Excerpt: Pigment and Epistemology, Craig Burnett, 2017

Luca Bertolo has lived in Milano, São Paulo, London, Berlin and Vienna and from 2006 he lives in a village on the Apuan Alps. Has shown his works in public institutions and private galleries among which MART, Rovereto; GAM, Torino; GNAM, Roma; Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge; Centro Luigi Pecci, Prato; MACRO, Rome; Nomas Foundation, Rome; SpazioA, Pistoia; Arcade, London/Bruxelles; Fondazione Prada, Milano; 176 / Zabludowicz Collection, London; Marc Foxx, Los Angeles; Galerie Tatjana Pieters, Ghent; The Goma, Madrid. Since 2010 Bertolo has contributed several articles to italian art magazines. A collection of his texts on art has been recently published: I baffi del bambino. Scritti sull’arte e sugli artisti, Quodlibet, 2018. Since 2010 has taught Painting at the Accademia di Belle Arti of Bologna and Florence.

Walter Swennen (b. 1946, Brussels, BE) lives and works in Brussels.

Walter Swennen is known for his radical, experiential and associative approach to painting, which is perhaps best summarised as a belief in the total autonomy of the artwork. For Swennen, a painting does not need to be ‘emotive’ or ‘understood’: the primary goal of painting is, quite simply, painting. Everything – form, colour, subject – comes from the outside. A poet before he became a painter, it is no coincidence that language plays a vital role in his practice. In the early 1980s, Swennen stopped writing poetry and switched to painting as his primary means of expression. Although his oeuvre varies greatly in scale, style and materials, it can be construed as an on-going exploration into the nature and problems of painting (its potential and limitations), the fundamental question of what to paint (subject matter), and how (technique). Often working on supports made from found objects, such as sheets of old

plastic or salvaged wood, Swennen allows his chosen imagery to float loosely atop a background made up of more allusive elements, such as blocks of colour, dripped paint or unusual textures. The images he deploys are often derived from popular culture, advertising and magazines, or take the shape of everyday objects such as wine bottles or bicycles. The way that he handles motifs – he takes them as he finds them, high or low, and manipulates them at will – is akin to a kind of visual poetry that harks back to his early career as a writer. Freely associative, and above all humorous, Swennen’s paintings explore the relationship between symbols, legibility, meaning and pictorial treatment.

A major retrospective will be held at Kunstmuseum Bonn in 2021, traveling to Gemeentemuseum Den Haag and Kunst Museum Winterthur. Solo exhibitions include La pittura farà da sé, La Triennale di Milano, Milan (2018); Ein perfektes Alibi, Kunstverein für die Rheinlande und Westfalen, Düsseldorf (2015); So Far So Good, WIELS, Brussels (2013-14); Continuer, Culturgest Lisbon (2013); Garibaldi Slept Here, Kunstverein Freiburg (2012) and How To Paint A Horse, Cultuurcentrum Strombeek and De Garage, Mechelen (2008)

Clive Hodgson (1953, UK) lives and works in London.

Hodgson studied at St. Martin’s School of Art, London, UK (1971-72), the Slade School of Art, London, UK (1972-77) and in 1998 he was awarded the residency at the British School at Rome. Recent exhibitions include: Fieldwork, 42 Carlton Place, Glasgow, UK (2020); Ordinary Reality, Palazzo de’ Toschi, Bologna, IT curated by Davide Ferri (2020); The Electrician’s Nightmare, Tatjana Pieters Gallery, Ghent, BE (2019); Still Life, Arcade, London, UK (2019). His 1st solo exhibition in Brussels is scheduled to open with Arcade in November 2020.

“The blatancy of recent abstractions by Clive Hodgson is perhaps a function of the sheer urge to make painting ‘difficult’ again, in a time when almost anything seems assimilable into the open field of contemporary art. It is hard to imagine any painting creating the sort of unease today that Hélion’s or Guston’s style shifts did. Yet Hodgson’s refusal of any ‘touch’, his ultra-thin application straight onto white primer, and his use of ornamentalism, are all truly and excitingly disconcerting. What emerges is the ability of colour, form, structure, illusion and expressive mark to assert themselves even in the absence of any ‘simpatico’ handling. The pictures come alive; and the mysterious terms in which a painting succeeds or fails (or both simultaneously) are themselves partly the object of the work’s investigations. Remarkable, too, is that such empirical pictorial experiments are not lacking in wit, humanity even poignancy.”

– Merlin James

Merlin James (1960, Cardiff, UK) lives in Glasgow.

Selected solo exhibitions: OCT Boxes Museum, Shunde & OCT Art and Design Gallery, Shenzhen (2018); CCA Glasgow (2016);; Kunstverein Freiburg (2014); Parasol Unit, London (2013); KW Institute, Berlin (2013); Douglas Hyde Gallery, Dublin (2012); New York Studio School (2007); 52nd Venice Biennale, Wales Pavilion (2007); Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge (1996); National Gallery of Wales (1995). He has written and lectured extensively on art. Published lectures include the Kingston University Stanley Picker Lecture at the Tate Gallery (1996) entitled ‘The Non-Existence of Art Criticism’, and the Alex Katz Chair in Painting lecture, given at The Cooper Union, New York (2002) entitled ‘Painting Per Se’.

“Merlin James has quietly established himself as one of the more interesting painters around, as well as one of the best critics of painting. His work might be taken for that of a nostalgic academic or a postmodern pluralist, but the very fact that these two distinct, if not opposed, identities present themselves suggests that settling on either one would be a misprision of his project. It`s true that his paintings dredge up styles from the past, and lots of them at that, but he neither invokes them as eternal verities nor toys with them with insouciant lightness. Rather, James dwells on painting`s multiplicity as its great fact and great mystery – meaning that even its finest exemplars convey no more than part of its truth, while even journeymen can sometimes surpass themselves. In James`s work, humor, poetry, mental gamesmanship, and a sense of reserve that is nonetheless unashamed of sentiment never conceal that homage to past masters is always a deformation.”

– Barry Schwabsky

Winifred Nicholson (21 December 1893 – 5 March 1981)

Nicholson was born Winifred Roberts in Oxford. She studied in London and Paris before marrying Ben Nicholson in 1920. She exhibited with her husband in the 1920s and was a member of the Seven & Five Society between 1925 and 1935. In 1937 she contributed to ‘Circle’ under the name of Dacre. After the war she settled in Cumbria.

For further information visit: www.winifrednicholson.com

With thanks to Kettle’s Yard, Cambridge and the Trustees of Winifred Nicholson.

Phoebe Unwin (b. 1979, Cambridge, UK) lives and works in London

“Not what something looks like… more what something feels like? Phoebe Unwin’s paintings acknowledge the actuality of inhabited places, lived encounters and memorable events, but they also clear their own perceptual and sensory space, creating new visual realties from the felt resonance of recalled experience. We might think of them as uniquely sensitive representations: as if vivid intensities of colour and light, rather than verifiable forms, were all our eyes could detect. Or perhaps they are representations of sensory uniqueness: pictures that pick up on the interdeterminate, indescribable effects of being precisely somewhere, or being with a specific someone. They seize a decisive something from the fleeting, unrepeatable interplay between inner and outer states.”

Excerpt: Field / Phoebe Unwin, Silvana Editoriale, 2019, Declan Long

Unwin studied at Newcastle University (1998-2002) and The Slade School of Fine Art (2003-2005). Recent solo exhibitions include Iris, Towner Gallery, Eastbourne, UK (2019); Field, Maramotti Collection, Reggio Emilia, Italy (2018); Pregnant Landscape, Amanda Wilkinson Gallery, London, UK (2018).

Unwin’s work is held in public collections including Tate, London; Maramotti Collection, Reggio Emilia, Italy; Arts Council Collection, UK; British Council Collection; Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, The Netherlands; Southampton City Art Gallery; The Government Art Collection, UK and The Yale Centre for British Art, New Haven, USA.

For further information visit: www.phoebeunwin.com

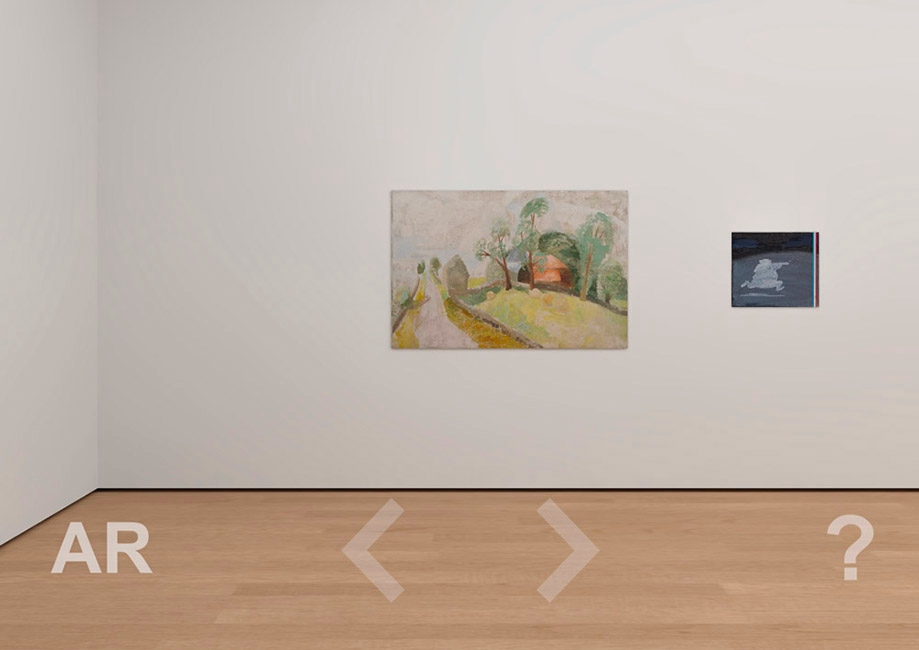

Winifred Nicholson

Sam Graces

1928

oil on board

53 x 61 cm

Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge

© Trustees of Winifred Nicholson

Walter Swennen

Poker Face

2020

oil on canvas

127 x 109 cm

Merlin James

Hair

2013

oil and hair on canvas

52 x 85 cm

Clive Hodgson

Untitled

2008

acrylic on canvas

35 x 30 cm

Phoebe Unwin

Encounter

2019

oil on canvas

60 x 50 cm

Merlin James

Untitled (Head)

2007

acrylic on canvas

55.8 x 82.5 cm

Luca Bertolo

google+search+images+fleeing

2016

oil on canvas

250 x 200 cm

Phoebe Unwin

Bedroom

2018

oil on canvas

66 x 82 cm

Luca Bertolo

Natura Morta (Still Life) 19#02

2019

oil on canvas

45 x 40 cm

Clive Hodgson

Untitled

2019

oil on canvas

40 x 35 cm

Walter Swennen

Le Chasseur Français

2020

oil on canvas

60 x 70 cm

Winifred Nicholson

Roman Road

1926

oil on canvas

126.5 x 189.5 cm

Kettle’s Yard, University of Cambridge

© Trustees of Winifred Nicholson

Luca Bertolo

Terzo paesaggio #22

2019

oil on canvas

60 x 50 cm

Phoebe Unwin

Building

2018

india ink and acrylic on canvas

183 x 153 cm

Clive Hodgson

Untitled

2014

acrylic on canvas

213 x 160 cm

Merlin James

Untitled (Head)

2007

acrylic on canvas

55.8 x 62.5 cm

Phoebe Unwin

Shutter

2018

oil on canvas

70 x 60 cm

Luca Bertolo

Terzo Paesaggio #13

2019

oil on canvas on canvas

70 x 80 cm

Walter Swennen

The Dark House

2020

oil on canvas

30 x 24 cm