Richard Rorty

Maria Zahle

I grew up knowing that all decent people were, if not Trotskyites, at least socialists. I knew that poor people would always be oppressed until capitalism was overcome. So, at 12, I knew that the point of being human was to spend one’s life fighting social injustice.

My cousin Adam might ask me: how does your work as an artist fit into your politics? The answer: it doesn’t.

I was not quite sure why those orchids were so important, but I was convinced that they were. I was uneasily aware, however, that there was something a bit dubious about this esotericism – this interest in socially useless flowers. I was afraid that Trotsky would not have approved of my interest in orchids.

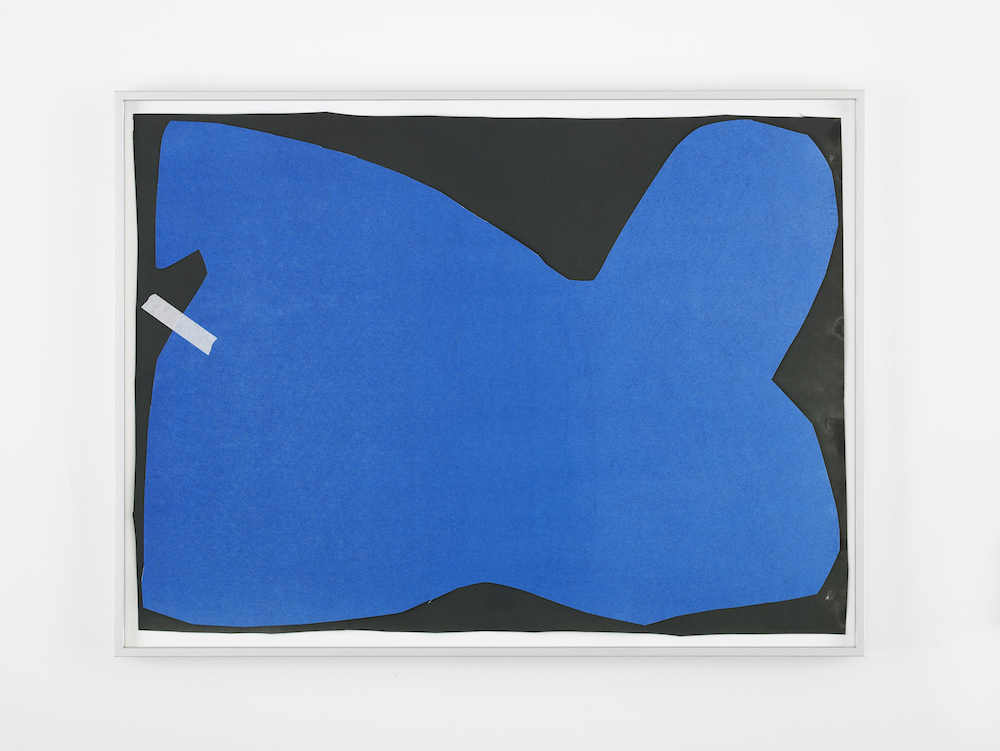

I recall a crit where I asked my tutor to explain to me what subject matter was. She got angry, and refused to comply. I was being belligerent, of course, but in a way, I still don’t quite understand what subject matter is. I mean, it’s not the work, so what good does it do? To me making art is about developing a structure which can exist spatially, realistically, with me. The Ocean collages are made in this very physical way, often on the floor, where I mess around with tape, scissors, and paper without quite knowing where the process will take me. It’s an enjoyment of touch and colour, the hand leading the way towards something which might be an image, and might just be a display of raw material.

Insofar as I had any project in mind, it was to reconcile Trotsky and the orchids. I wanted to find some intellectual or aesthetic framework which would let me – in a thrilling phrase which I came across in Yeats – ‘hold reality and justice in a single vision’. By reality I meant, more or less, the moments in which I had felt touched by something numinous, something of ineffable importance. By justice I meant the liberation of the weak from the strong. I wanted a way to be both an intellectual and spiritual snob and friend of humanity – a nerdy recluse and a fighter for justice.

Zeeeyow! I think as the brightly coloured liquid runs off the edge of the paper and back into the tub, leaving the paper shiny, blue, and my fingers messy and wet. The room fills up with rectangles of dripping orange, yellow, green, black, and pink. It’s a dense forest of colour. I weave in and out amongst the rows of paper to find the last free spots for the final dips. Is it numinous, ineffable? Yes, yes. It is.

I gradually decided that the whole idea of holding reality and justice in a single vision been a mistake. By now I am pretty sure that looking for such a presence and such a vision is a bad idea. The main trouble is that you might succeed, and your success might let you imagine that you have something more to rely on than the tolerance and decency of your fellow human beings.

I have a loom in my studio and another one at home. While working at home Sixten comes and sits next to me on the bench. He wants to weave too, and I show him how to step on the treadle before pushing the shuttle through the shed of yarn that opens up in front of us. He’s so short that while standing on the treadle he can’t quite reach. Mildly disappointed, he moves off the loom, and I keep working for a while. Later, he finds a turquoise roll of yarn on the floor and he uses it to hang up a series of paper flags we were making that day.

All Richard Rorty quotes are taken from the essay Trotsky and the Wild Orchids (1992) published in Richard Rorty: Philosophy and Social Hope

Ocean

2018

hand coloured paper collage, archival tape, aluminium frame

59.5 x 79 cm

Ocean

2018

hand coloured paper collage, archival tape, aluminium frame

59.5 x 79 cm

Ocean

2018

hand coloured paper collage, archival tape, aluminium frame

59.5 x 79 cm

Ocean

2018

hand coloured paper collage, archival tape, aluminium frame

59.5 x 79 cm

Ocean

2018

hand coloured paper collage, archival tape, aluminium frame

59.5 x 79 cm

Ocean

2018

hand coloured paper collage, archival tape, aluminium frame

59.5 x 79 cm

Ocean

2018

hand coloured paper collage, archival tape, aluminium frame

59.5 x 79 cm

Ocean

2018

hand coloured paper collage, archival tape, aluminium frame

59.5 x 79 cm

Trotsky and the Wild Orchids

2018

Handwoven flax, cotton, wire, pyrite, pewter, bronze

43 x 96 x 56 cm

Trotsky and the Wild Orchids

2018

Handwoven flax, cotton, wire, pyrite, pewter, bronze

43 x 96 x 56 cm

Trotsky and the Wild Orchids (detail)

2018

Handwoven flax, cotton, wire, pyrite, pewter, bronze

43 x 96 x 56 cm